|

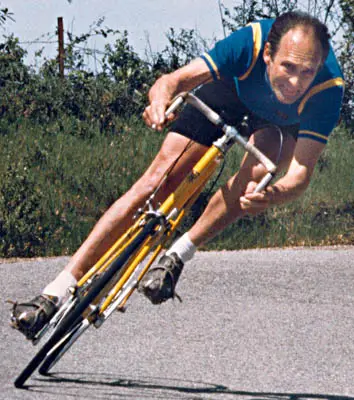

Jobst Brandt testing Avocet slicks

Subject: Tires with Smooth Tread

From: Jobst Brandt

Date: December 5, 1997

Drag racers first recognized the traction benefit of slick tires, whose benefit they could readily verify by elapsed times for the standing-start quarter mile. In spite of compelling evidence of improved traction, more than twenty years passed before slicks were commonly used for racing cars, and another twenty before they reached racing motorcycles. Today, slicks are used in all weather on most street motorcycles. In spite of this, here at the end of the millennium, 100 years after John Dunlop invented the pneumatic tire for his own bicycle, bicyclists have not yet accepted smooth tread.

Commercial aircraft, and especially motorcycles, demonstrate that a round cross-section tire, like the bicycle tire, has an ideal shape to prevent hydroplaning. The contact patch, a pointed canoe shape, displaces water exceptionally well. In spite of this, hydroplaning seems to be a primary concern for riders who are afraid to use smooth tires. After assurances from motorcycle and aircraft examples, slipperiness on wet pavement appears as the next hurdle.

Benefits of smooth tread are not easily demonstrated because most bicycle riders seldom ride near the limit of traction in either curves or braking. There is no simple measure of elapsed time or lean angle that clearly demonstrates any advantage, partly because skill among riders varies greatly. However, machines that measure traction show that smooth tires corner better on both wet and dry pavement. In such tests, other things being equal, smooth tires achieve greater lean angles while having lower rolling resistance.

Tread patterns have no effect on surfaces in which they leave no impression. That is to say, if the road is harder than the tire, a tread pattern does not improve traction. That smooth tires have better dry traction is probably accepted by most bicyclists, but wet pavement still appears to raise doubts even though motorcycles have shown that tread patterns do not improve wet traction.

A window-cleaning squeegee demonstrates this effect well. Even with a new sharp edge, it glides effortlessly over wet glass, leaving a microscopic layer of water behind to evaporate. On a second swipe, the squeegee sticks to the dry glass. This example should make apparent that the lubricating water layer cannot be removed by a tire tread, and that only the micro-grit of the road surface can penetrate this layer to give traction. For this reason, metal plates, paint stripes, and railway tracks are incorrigibly slippery.

Besides having better wet and dry traction, smooth tread also has lower rolling resistance, because its rubber does not deform into tread voids. Rubber, being essentially incompressible, deforms like a water-filled balloon, changing shape, but not volume. Rubber of a tire with tread voids bulges under load and rebounds with less force than the deforming force. This internal damping causes the energy losses of rolling resistance. In contrast, the smooth tread transmits the load to the loss-free pneumatic compliance of the tire.

In curves, tread features squirm to allow walking and ultimately, early breakout. This is best demonstrated on knobby MTB tires, some of which track so poorly that they are difficult to ride no-hands.

Although knobby wheelbarrow tires serve only to trap dirt, smooth tires may yet be accepted there sooner than for bicycles.

![]()

![]()

More Articles by Jobst Brandt

Next: Wiping Tires

Previous: Rolling Resistance of Tires

![]()

![]()

Last Updated: by John Allen