|

|

|

![]()

![]()

A Sturmey-Archer drum brake

This article is about drum brakes. For suggestions on better and less good brake technologies for different kinds of bikes (kids, casual, touring, tandems, mountain bikes, road-racing, etc.) start with the main article about brakes. Also see the section about brake levers in the article about direct-pull brakes and the article on cables.

A drum brake is a hand-lever-operated hub brake with brake shoes that press against the inside of a cylindrical drum. Drum brakes were once the most common type for motor vehicles, though disc brakes are now more common. Drum brakes are popular on utility bicycles in countries with wet weather; much less so for recreational and racing use, where rim brakes predominate and disc brakes are becoming more popular.

A drum brake may be an integral part of a hub, or may thread onto the left side of the hub the same way a freewheel threads onto the right side. Since the torque from the brake is opposite that from a freewheel, the threads are right-handed, like those for the freewheel.

A front drum brake may be combined with a hub generator, and a rear drum brake, with an internal-gear hub. Special, large drum brakes have been used as drag brakes on tandems for heat dissipation on downhill runs.

A Shimano Rollerbrake is a special kind of drum brake and is covered in a separate article.

A drum brake has two brake shoes opposite one another, actuated by a mechanism which pushes them apart at one or both ends. Their pressing outward against the inside of the drum produces friction. The drum is part of the hub shell, or is attached to it, and slows the wheel. The brake shoes are mounted on a backing plate which is attached to the hub axle and to a reaction arm connected to the frame or fork to resist torque. When the brake is released, springs pull the brake shoes inward, away from the brake drum.

Most automotive drum brakes are operated by hydraulic pistons, but bicycle drum brakes use a cable with a linkage to a cam that pushes the brake shoes outward. The photo below shows a Sturmey-Archer drum brake partially disassembled. The hub shell with the drum is at the top and the brake shoes on their backing plate are at the bottom.

The photo below highlights the location of a pivot (blue arrow) which has a snap ring allowing removal and replacement of the brake shoes. A spring is hidden under the brake shoes, except for its ends, highlighted by the green arrows. The spring retracts the brake shoes when the brake is released.

The next picture shows how a lever rotates the cam (red arrow) and spreads the brake shoes. When the brake is in use, the cable housing attaches at the C-shaped fitting which my thumb is holding, and the inner wire of the cable is clamped to the end of the lever. The hole at the end of the reaction arm is for a clamp band that secures the reaction arm to the frame or fork.

The shape of the cam affects the operation of the brake. As the elongated cam of this brake (typical of bicycle drum brakes) turns to apply the brake harder, the mechanical advantage increases. The hand lever must be pulled farther, and the force therefore does not increase as quickly as might be expected. Also as the brake shoes wear, the mechanical advantage increases. A cam with a spiral-shaped surface on each side would result in a linear relationship, more like that of other brakes, but also increased friction, so the cam might not retract the shoes, cable or hand lever.

Bicycle brakes use a simplex mechanism for the sake of mechanical simplicity. One end of each brake shoe is attached to a pivot, hardly moves outward, and wears little. The leading shoe is the one where the brake drum is rotating toward the pivot; vice versa for the trailing shoe. The rotation of the drum tends to make the leading shoe "dig in," pressing harder against the drum, and removing some load from the cam, while the corresponding effect on the trailing shoe tends to reduce its load on the pivot and put additional load on the cam. At first, the leading shoe wears faster, but the cam produces equal displacement of both shoes (give or take the small difference in radius at which the cam acts). For this reason, the force on the two shoes, and the wear, equalize themselves once the brake has worn in.

Which shoe is the leading one depends on whether the wheel is rolling forward or backward. A bicycle brake is used mostly when rolling forward, though also to prevent the bicycle from rolling backward when stopped facing uphill.

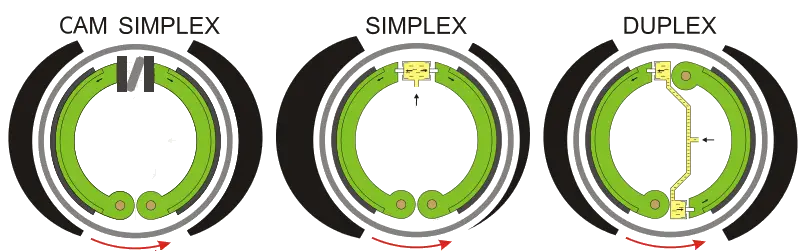

The illustration below represents cam actuation as well as two types of hydraulic actuation, which produces equal force rather than equal displacement at the brake shoes. The duplex type has, in effect, two leading shoes. The duplex type, unlike the simplex, is much less effective when the vehicle is traveling backward than when it is traveling forward. Can you see why?

Drum brake types. The black crescents outside the drum

are graphs of the pressure of the brake shoes against the drum.

Illustration CC by SA 4.0 by Wikipedia contributor A7N8X, modified.

![]()

![]()

All in all, the better drum brakes can be a good choice on bicycles which are ridden in flatlands and wet weather -- typically, urban conditions, and more so on the rear wheel than the front.

![]()

![]()

One-sided mounting results in an unbalanced load on the front fork, potentially leading to handling issues. The load on the fork is heavy because the reaction arm takes up the torque from braking at a relatively short distance from the hub. However, a drum brake does not tend to pull the front hub out of the fork like a disc brake, because the backing plate and drum are both connected to the axle, Forces from the brake shoes and drum are equal and opposite at the axle and cancel each other out, so the reaction arm resists only torque. As mentioned, with a strong front drum brake, though, the torque may be enough to flex the fork, causing "brake steer" or even bending a fork blade.

It goes without saying that the cable to any front hub brake on a suspension fork must be run in housing, but the cable to a front hub brake with a rigid fork must also be run in housing, because flexing of the fork during braking can tighten an open cable and lock the brake.

Someone didn't read our advice on cable routing.

DO NOT RUN AN OPEN CABLE TO A FRONT HUB BRAKE!

The rear cable is a bit long too, but that isn't a killer.

Older brake-shoe linings generally contain asbestos, which causes lung cancer. Avoid breathing the dust from these linings.

And, as mentioned, typical drum brakes do not dissipate heat well enough to avoid brake fade or vaporizing the grease in the hub bearings, if used for speed control on long downhills.

![]()

![]()

A drum brake that is integral with the hub must of course be built into a wheel. The spokes must be crossed on the brake side of the hub to withstand the torque from the hub. A low cross number may be needed to avoid an excessive rim entry angle with a large-diameter of the drum and small wheel.

Most drum brakes use the same brake levers as caliper brakes. Some may work better with longer-travel levers, but also note the pulley trick described below.

The cable, as already mentioned, must run in housing to a front drum brake, but an open cable may run to a rear drum brake.

Apply the brake when tightening down the locknut that secures the brake-shoe backing plate. If an open cable runs to the brake, you will need to use another cable (in housing) for this step, as the left axle nut must still be loose. This step centers the brake shoes so they contact the drum evenly and equally.

Tighten the axle nuts and reaction arm in steps, so they don't cause each other to bind before reaching their final positions. The reaction arm must be securely bolted to a part of the fork or frame capable of resisting the torque. Attachment should be with a clip that cinches tightly and prevents the reaction arm from rotating even a little bit if the brake is applied when the bicycle is facing uphill or rolling backward. Repeated back-and-forth motion of the reaction arm will loosen the axle nuts. Some bicycles have a "Pac Man" fitting on the left chainstay, so the reaction arm can simply be slid into and out of position; and also, there may be a quick release for the cable.

Cable quick release for a drum brake

In the photo below, an old Sturmey-Archer steel pulley doubles the cable travel and mechanical advantage with an (also old) Atom drum brake and serves as a cable quick release. The same trick is possible with the larger pulley of a Problem Solvers Travel Agent, avoiding the use of its smaller pulley, which would more quickly cause metal fatigue to the cable.

Pulley as cable-travel doubler and quick release

A drum-brake hub requires the same bearing maintenance as other hubs, and occasional cable adjustment as the brake shoes wear. If cable adjustment does not restore brake performance, the brake should be disassembled to check the shoes for wear and contamination. Often, the problem is that they have glazed, and a light sanding will cure the problem, but beware of asbestos with older brake linings.

![]()

![]()

Last Updated: by John Allen