|

Different cyclists have different leg lengths. It seems obvious that crank length should be proportional, so long-legged cyclists should have long cranks, short-legged cyclists should have short cranks....and yet, 99.9% of adult bicycles have crank lengths between 165 and 175 mm. Have the bicycle manufacturers joined in a great conspiracy to force everybody to ride the same length cranks, regardless of their needs?

Crank lengths: TA cranks, 155 and 170mm; between them, a 4-inch

(102mm) crank from a Raleigh child's bicycle, modified for use on a tandem

kidback adapter. John Allen's son used this crank starting at age 2 1/2.

This is a common misunderstanding. The "leverage" of a bicycle drive train, also known as "gain ratio" depends on the crank length, wheel diameter and the sizes of both sprockets.

Yes, if you go to longer cranks without changing any of the other variables, you will have more "leverage", which is another way of saying you'll have a lower effective gear...but on a multi-speed bike, you can change gears at will!

Ay, there's the rub! Assuming you adjust your gearing appropriately, crank length has no effect on leverage, it just has to do with the range of motion of the knee and hip joints.

Too long cranks cause excessive knee flex, and can cause pain/injury if it causes your knee to flex more than it is used to.

I learned this the hard way when I bought a used mountain bike that came with 180 mm cranks. I found that it made my knees hurt every time I rode it.

On the other hand, there doesn't seem to be any deleterious effect from shorter cranks.

I've been experimenting with this a bit myself lately. For my fixed gear, I commonly ride 165 mm cranks with a 42/15 ratio on 700C or 27 inch wheels, when I'm riding fixed. This gives a gain ratio of 5.8.

My latest experiment is taking place on plastic Trek frame I picked up in a barter deal. I had a pair of TA 150 cranks that used to be on my kids' Cinelli BMX bike, so I've put these on the Trek. I'm running a 45/17, which gives a gain ratio of 5.9, just a bit higher.

When I first get on the bike after riding with longer cranks, it feels a bit funny at first, but within a very short distance it's just fine. I go just as fast, climb just as well. For a given speed, my pedal rpm is higher (though my pedal speed is the same) but the short cranks make it easy to spin much faster than I normally would.

After riding this bike for a few miles, "normal" cranks feel a bit weird and long at first, then I get used to them after riding a couple of minutes.

Crank length is measured between the pedal hole and spindle hole, center to center and perpendicular to the spindle. Almost all crank lengths are multiples of 5 mm, making super-accurate measurement unnecessary. Some older British cranks are in inch sizes. Many cranks carry markings identifying the length. The photo at the left shows the markings on the back of a Shimano crank, and the photo above right shows markings for the 155mm TA crank. The "W", unique with TA, indicates British pedal threading.

I think people really obsess too much about crank length. After all, we all use the same staircases, whether we have long or short legs. Short-legged people acclimate their knees to a greater angle of flex to climb stairways, and can also handle proportionally longer cranks than taller people normally use.

![]()

![]()

Riders who have one leg longer than the other sometimes attempt to compensate for this by using a shorter crank on the side with the shorter leg. I do not recommend this, however.

When one leg is significantly shorter than another, the shorter leg is also usually weaker than the longer one. Since a short crank results in a higher gain ratio, this setup would ask the the weaker leg to push harder than the stronger one.

A better way to deal with significant leg-length discrepancies is to build up the sole of the shoe, or to use longer bolts and spacer washers between the cleat and the shoe sole, or to build up the pedal by some sort of add-on attachment.

Leg-length discrepancy can also be somewhat accommodated by putting the cleat on the foot with the longer leg farther back toward the heel.

In some instances, deliberately setting the saddle slightly askew might also help.

In general, for any given rider, the shorter the cranks are, the easier it becomes to spin a rapid cadence. If the rider who prefers a faster cadence gets longer cranks, this will develop a preference for a slightly slower cadence. If the rider who prefers a slower cadence gets shorter cranks, it will become easier to pedal at a faster rate. The most common crank length is 170 mm. This is what comes stock on most tandems. If you find that you have serious cadence incompatibility, start by installing 175 mm cranks for the rider who wants a faster cadence. If this helps, but not enough, get 165 mm cranks for the rider who has trouble pedaling fast.

Note, changing the crank length doesn't directly change the cadence, and both riders will still be pedaling at the same cadence, but the longer cranks will encourage the "spinner" to slow down a bit, and the shorter cranks will make it easier for the "slogger" to keep up.

![]()

![]()

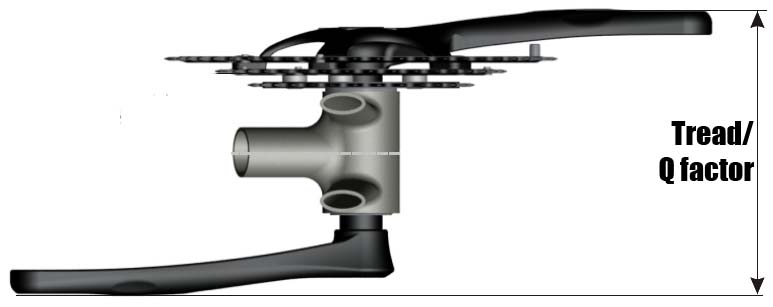

The tread, or "Q factor" of a crankset is the horizontal width of the cranks, measured from where the pedals screw in. The wider the tread, the farther apart your feet will be. It is generally considered a good idea to keep the tread fairly narrow.

There are three main reasons for this:

Bicycles with a single chainwheel, including "1x" derailer systems with a very wide range of sprockets at the rear wheel allow the right crank to be somewhat closer to the centerline of the frame.

The term "Q factor" was originated by Grant Peterson, then of Bridgestone, now of Rivendell; his 1991 article about it.

![]()

![]()

Most older cranks were shaped so that they were basically parallel to the centerline of the bicycle.

Older cranks

Starting in the 1980s, there was a movement toward "low-profile" cranks. With low-profile cranks, the pedal ends of the arms stay in the same place, but the axle is shortened and the arms run at an angle, outward from the bottom bracket toward the pedal end.

Low-profile cranks, which work with a shorter bottom-btacket spindle

Low-profile cranks save a bit of weight, and are also potentially stiffer. The design is a real benefit to riders who have a splay-footed (toes-out) pedaling style, avoiding interference between the rider's heels/ankles and the crank.

Some people are down on low profile cranks because they blame the design for the wider tread seen on newer cranks, but that's not an accurate analysis. The wider tread came first, for reasons mentioned above. The silver lining in the wider tread "cloud" is that it makes low-profile cranks possible with standard frame dimensions.

For reasons that are not completely clear, many recumbent riders benefit from shorter-than-usual cranks. Some people who have no knee problems on upright bikes find that their knees pain them when they ride a recumbent. Shorter cranks can often alleviate this, though it isn't clear that the length of the cranks itself is the cause of the problem.

One theory is that the knee pain results from pushing harder, "lugging" in a too-high gear. With an upright bike, if you push very hard, you are lifted up from the saddle, so you know you are doing so. With a recumbent, where you are braced against the back of the seat, it may not be so easy to judge how hard you are pedaling, so you may just overstrain your knees by pushing too high a gear without realizing it.

Crank damage is of several types:

A broken crank. Note the "beaches" where the crack grew, step by step,

and the rough area where the crank finally gave way. The crank's cross-section

is not ideal to resist bending and torsion, and it is anodized,

possibly promoting crack formation -- see Jobst Brandt's comments about

anodization of rims.

The bend is between the axle attachment and pedal attachment. It can be measured only if the crank is installed on a bicycle and a straight pedal axle is installed. It could be worth a shop's doing this test if it does a lot of repair work

You need to make a tool. Drill a hole into the end of an aluminum rod to fit as an extension to a pedal axle and improve precision of measurement. The drilled hole needs to fit snugly onto the pedal axle. Creation of this tool requires a lathe, but this one-time job can be taken out to a machine shop. The extension needs to point straight out. (Check that it doesn't wobble as the pedal is threaded in.)

Place the bicycle on a workstand. Tighten the tool onto the crank. Rotate the crank. Does the angle of the extension (deviation from perpendicular) change relative to the seat tube when the crank is rotated? This can usually be determined by visual inspection, but if not, rig up a reference plane (something as simple as a cardboard box taped to the frame) that protrudes from the side of the bicycle, and measure the distance between it and the inner and outer ends of the extension at four angles of crank rotation with the crank parallel and perpendicular to the plane. There is no need for the plane to be aligned carefully perpendicular to the centerline of the frame, because you need only calculate the difference between measurements.

![]()

![]()

Last Updated: by John Allen