|

When recording using more than one device (audio and/or video) at once, you must synchronize their output for editing. In my bicycle videos, I use forward-facing and rearward-facing cameras at the same time, and cameras mounted on different bicycles. Synchronizing 2D video is relatively easy. Stereo or surround sound from multiple devices requires tight synchronization and special equipment or techniques. This article describes them, and the remarkable results which are achievable, even real surround sound without a multi-channel recorder.

Control of some of the newer action cameras, more than one at a time, is possible using wi-fi with a dedicated controller or smartphone. Control may offer simultaneous starting and stopping, and even multiple views on a screen. Wi-fi will work with cameras on a single bicycle, controlled by the rider, or with people riding within a few meters of one another. If you are in the market for cameras, you might check for this feature.

A high-tech way to synchronize video and audio recordings is called time code. Time code traditionally uses a timing signal sent over cables and recorded along with the audio and video. Time code can control the playback speed of analog audio tape, and can fast-forward and rewind tapes to synchronize them with each other.

Time code also may be sent and received using wireless devices, but as of now, no consumer-grade action camera supports this feature.

Some professional-grade equipment derives time code from GPS satellite signals. This only works where GPS signals can penetrate -- generally, not inside buildings -- and is expensive and complicated to use. GPS can synchronize any number of cameras, anywhere on Planet Earth. GPS can also identify the location of a device to within a few meters, and the direction in which a camera is pointing, if it is moving.

Some newer action cameras record a GPS track and time stamp, which may be used to align recordings in post-processing. This is generally a high-end feature.

I expect that a smartphone app will be offering GPS timing sooner rather than later, but smartphone cameras are rather limited, and this feature would be more useful in a dedicated camera.

![]()

![]()

How do we synchronize when shooting on a budget, lacking time code?

We fall back on the classic synchronizing technique used in film: a marker visible in the image and audible in the sound track. Bicycle video takes are generally rather long – you start recording, and then ride – so setting this marker isn't much of an inconvenience.

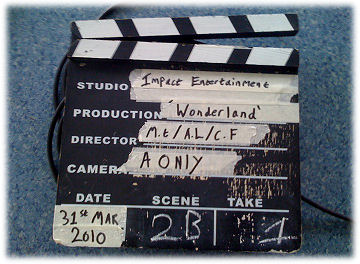

A traditional wooden clapperboard

The clapperboard – with its chalkboard to indicate a take number – is the time-honored time-alignment tool in the motion-picture industry. The clapperboard provides a timing reference at the start of a take. The speed of sprocketed film and audio tape is set by the power-line frequency. Once clips are aligned on the editing table, they remain in sync.

I use video cameras which record audio, so there's no need for a clapperboard's written identification of the take. I make a verbal announcement instead. For synchronization, I use a hand clap, visible to every camera and recorded in every sound track. If I am using two cameras on my helmet to get front and rear views, I back up to a window so the rear-facing camera shows the reflection of my clapping hands, or I tap the side of the helmet to shake the image from the helmet camera and make a sound. With cameras in other locations, I walk around and clap so my hands are also visible in my helmet camera. Then I have a cue in every recording.

In the short video clip above, the main image is from a camera on my helmet. The picture-in-picture is from a camera duct-taped to the rear rack of a friend's bicycle. My camera is looking forward at him and his is looking back at me. You see and hear the hand clap, and then hear my short announcement identifying the take. Here is a still of the frame of the video where my hands come together:

The timing of modern video cameras and digital audio recorders is set by precise quartz-crystal electronic clocks. We can thank documentary filmmaker Richard Leacock for introducing this use of crystal control. He used it with modified 8mm film and audio cassette recorders at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the early 1970s -- but there's no need any more to modify equipment. Cameras will typically run for several minutes before the images are out of sync by even one video frame, 1/25 or 1/30 second.

You could run a test on your cameras to determine how well the timing between them agrees. Record a hand clap at the beginning and end of a long clip and count the number of frames the timing drifts, if at all. I have had to add a duplicate frame once every 6 minutes to keep two of my cameras in sync..

Cameras generally record 4 gigabyte files, to use FAT32 data format, which is readable on a computer running MacOS, Windows or Linux. This means that every 10 minutes or so with HD 1080 video at 30 frames per second (longer or shorter time for other formats), a file must be saved and a new one started. (Memory cards can be reformatted to an extended FAT32 format if the camera supports it, to allow longer uninterrupted recordings.) Some cameras overlap the files or start the new one without skipping a frame. Others leave a gap of a few seconds. If you have a camera which leaves gaps, you are going to have to resynchronize clips after the first one with additional hand claps or random audio or video events -- which can be frustrating and time-consuming.

One example of a random event is the sight and sound of a car rolling over a manhole cover. Footsteps also are good. Aligning on speech is harder, though the sound of the letter P begins when mouth opens suddenly, and the waveform in the sound track shows a sudden increase in volume. The letters B and M are less good, because the vocal cords are vibrating before the mouth opens, but may be usable. If you do much aligning on speech, you will find that you are beginning to learn to read lips!

In post-processing, I align the clips as described below.

![]()

![]()

Now, for a bit of technical background to help you use the hand-clap technique when editing video.

A video consists of a series of frames (individual images) shown one after another quickly enough to create the illusion of motion. The rate is typically 30 frames per second (actually, 29.97 for color signals) in countries which use 60 Hertz (cycle per second) AC power; 25 frames per second in countries which use 50 Hertz AC power. The frame rate is nominally ½ the power-line frequency so that any effect of imperfect power-supply filtering stays in the same place in the image, or nearly, from one frame to the next, rather than causing annoying flicker or wobble.

Video editing is only by one-frame, 1/25 or 1/30 second, increments. Special software can adjust audio more precisely; and that may be desirable for some purposes. I'll discuss that later.

Some digital video storage formats align the audio to each frame. Other formats use keyframing, where the audio is tacked to the video only once every few frames. Between keyframes, these formats store the differences between images, resulting in smaller digital files. If a video clip doesn't start with a keyframe, the audio and video may start slightly out of step – and then they stay that way.

All of the better video editing software applications give you a way to realign tracks to adjust timing. To do this, you need a clear cue in every track -- preferably, your hand clap. You make your work easier by leaving cameras running, so you do not have to synchronize repeatedly.

There are applications which hunt through the audio and synchronize clips from different cameras, but they don't work for everything, and in particular not when the audio is very different or a camera is not recording audio.

For good synchronization on an audible cue, all microphones need to be within a few feet of each other. Sound travels only about 1100 feet (300 meters), per second, so a distant camera or microphone will record delayed audio – like when you see a dribbled basketball out of sync with its sound. A distance of only 30 feet or 10 meters will throw synchronization off by one video frame. Align a distant camera on the visual cue, rather than the audible one, then align its audio with that from the closer camera so the basketball dribbles in sync.

When editing, I first turn on the application's “audio scrubbing” function so I can hear the hand clap or other cue. I check the hand clap to see whether the audio and video from each camera are in sync. If not, I detach the audio so it is in a separate track. I zoom in on the editor's timeline until I can move back and forth one frame at a time and stop the motion at the hand clap. I set a marker for the hand clap separately for each audio and video track, then slide the tracks until all the markers align.

Moving video forward one frame at a time in a video editor plays the audio for the frame that is displayed. So, as I reach the same frame where the hands come together, I hear the sound of the clap, and see its sharp peak in the audio waveform display.

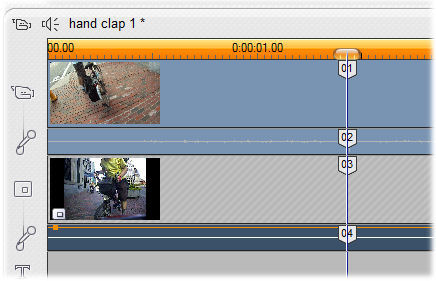

The image below is of the tracks from the video example above, in the editing suite Pinnacle Studio 12. In the thumbnail images, you can see the first frame of each video. The lower thumbnail holds an icon indicating that it contains a picture in picture. In the orange line near the top, each tick represents an individual frame of video. The cursor is aligned over four markers, which I placed at the hand clap frame in each video and audio track, then slid left or right until they lined up. The video in the lower track is grayed out because it is locked, so I can move the audio independently of it.

Hand clap editing in Pinnacle Studio v. 15

I align a take this way and save the resulting file. I don't use the same filename again. That way, I still have the original full-length take to re-use.

Note: Pinnacle 12 is an older version. In Pinnacle Studio 16 and up (at least through version 20), you can insert markers in an individual clip if it is open in the app's Effects Editor. Markers in the timeline will stay at the same time in the timeline, not move with clips. You may also fake a marker by trimming or splitting a clip at the hand clap. Setting markers will be different in other editing suites.

![]()

![]()

You might ask: with timing only to the nearest 1/25 or 1/30 second, will there be an echo? No! The sense of hearing and the frame rate of video are nicely matched. Humans hear an echo only if it is delayed by 1/30 of a second or more, a phenomenon called the “precedence effect” or the “Haas effect”, after the scientist who identified it. Two clips aligned to the nearest frame will be out of sync by no more than ½ frame, 1/50 or 1/60 of a second.

The error may either increase or decrease slowly over time if the camera speeds are very slightly different. Then you might choose the alignment so the error decreases as the take progresses. You choose one camera to be the reference, and drop or add a frame as needed in the other(s). The drift is rarely more than one frame every several minutes. As long as you are using audio from only one camera, this will not cause problems. If you are using audio from two or more cameras, it may -- see the section on speed correction, below, for solutions.

If you are especially picky about timing, then having cameras (not necessarily both of two) running at 50 or 60 frames per second allows you to bring the accuracy of synchronization to 1/100th of a second or less.

Sometimes, synchronization requires conversion of the video format due to peculiarities of the camera, editing software, or both. The Aiptek digital video recorder with my (early) helmetcamera.com camera recorded at the standard 29.97 frames per second, but Pinnacle Studio reported it as 25. Similarly, in Pinnacle Studio, an Insight POV HD helmet camera reported speeds slightly different from the 29.97 at which it recorded. Clips from these cameras did not stay in sync with others. Converting the files into another format solved the problem, so clips stayed in sync. I use AVS4YOU (commercial) and Handbrake (free) software to convert formats.

Using video with different frame rates leads to additional problems, and especially, jerky motion. Motion interpolation software addresses this problem; I have used Gooder Video MotionPerfect . Convert frame rates before synchronizing clips with one another.

If you are using the audio from only one camera, but another camera is running a tiny bit faster or slower, adding or dropping frames, as already described, works fine. Add or drop the frame where it won't be noticed in either the audio or the video..

Even if you are using a separate recorder only for audio, you should if possible have a video camera also recording audio, to provide a reference audio track for timing. If the speed difference between recorders is large enough that audio from the separate recorder goes noticeably out of sync with the reference, you need to realign it. If not combining it with other audio recorded at the same time and place, you don't need super-accurate alignment: counting video frames is good enough. It is easy to adjust the speed of an audio recording, rather than to edit it in one place after another to keep it in sync.

So, I establish one video/audio track as the reference, and adjust the speed of the audio recording(s) to match. Before adding or dropping frames in the non-reference video recordings, I separate the audio from the video onto separate tracks, so I can process it precisely. I copy the audio track(s) I have created so I still have the unprocessed audio to use when adding or dropping frames. To adjust speed, I use the free audio editing application Audacity -- available for Windows, the Macintosh and Linux. (Be sure that you have version 2.2.3 or later-- earlier versions had a bug in the Change Speed function). To adjust the audio speed:

When combining separate audio recordings made at the same time, in the same space, into stereo or surround sound, you need higher precision . The following paragraphs describe how to achieve that.

First, it matters how you record. Different level adjustment between audio channels causes shifts in the auditory image. To avoid this, use manual level control when recording, and adjust levels once you have combined tracks.

First, it matters how you record. Different level adjustment between audio channels causes shifts in the auditory image. To avoid this, use manual level control when recording, and adjust levels once you have combined tracks.

Steps in the high-precision alignment (below) are numbered to match those in the process described above, but are in a different order because more are performed in Audacity (or another audio editor): you derive the speed ratio by counting samples rather than frames. You will be dealing with some rather large numbers. You need a calculator that can display 10 or more places after the decimal point

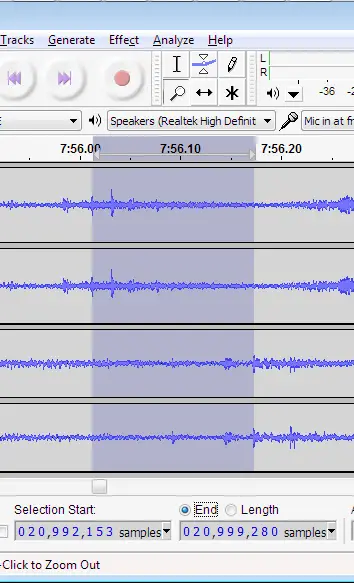

5. For high precision, you must export both the reference track and the track(s) you will adjust into an audio editing application (one at a time, muting all the other tracks and saving as audio). Impart the tracks into Audacity. The Audacity screen shot at the right is from two stereo tracks near the end of an 8-minute-long clip. Set the time display to read in samples, as shown.

2. Align your hand clap near the beginning of the clip so that it falls at the same time in all of the tracks. (If it is already in the same frame of video, it will be close, but we are going for precision here). Zoom in more and more, so finally you can shift one of the tracks backward or forward by one sample at a time.

4. Make a note of the time of the hand clap, in samples. Find your second hand clap (or another transient sound) near the end of the tracks, and select the time span between its occurrences, in the two tracks, as shown in the image. The numerical readout at the bottom of the image gives the time at the start and end of the selection. Next, calculate the ratio by which the speed of the lower track must be adjusted.

Selection End - Hand Clap Time

Selection Start - Hand Clap Time

This is your speed ratio. To maintain a steady stereo image over a long clip, you need to preserve several places after the decimal point. In an hour-long audio recording, at 48K, there are over 170 million samples, and you want the adjusted length to be accurate within a few samples. Save the calculated result for use in other clips from the same recorders (a text file is fine for this purpose).

You will need to adjust the entire length of this clip (and others), so you need to do a bit more calculation.

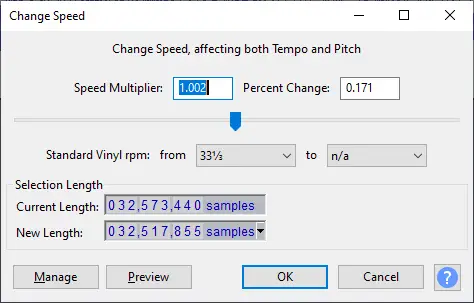

6. In your computer's calculator applet or on a hand-held calculator, calculate the new length, dividing the current length by the ratio you have calculated:

Current Length

Speed ratio

If this seems upside down to you, recall that, to increase the speed, you shorten the clip.

7: Select All and enter the new length in the New Length field in Audacity's Change Speed dialog box.  . Do not use the speed multiplier or Percent Change field: they round your numbers. (Also do not use a function which adjusts the speed while holding the pitch. That would produce some very odd stereo effects when tracks are combined.)

. Do not use the speed multiplier or Percent Change field: they round your numbers. (Also do not use a function which adjusts the speed while holding the pitch. That would produce some very odd stereo effects when tracks are combined.)

9.Readjust the sync of the hand clap (in Audacity, not in your video editing suite).. Alignment of the front and rear recordings within one or two milliseconds is easy to achieve if you have good cues (hand claps or others) in the audio. To keep sounds at the front from appearing at the rear, you may want to delay the rear recording by a few milliseconds -- somewhere on the order of 500 samples at the usual 44.1 or 48 k sample rates. You can check sync in Audacity. You shouldn't hear echoes unless they were in the original tracks.

8. Mute other track(s) and export the adjusted track(s) from Audacity.Though Audacity can display multiple tracks, it can output only one pair of stereo channels at a time, so export each track separately as a .WAV file (mute the other track when exporting). Each track will export starting at the zero time in Audacity. Import them into your video editing suite, starting at time zero. As already described, no echo will be audible if all the speakers produce the same sound within about 30 milliseconds (on video frame) of each other.

10. Check your work using headphones and surround loudspeakers. The tracks should stay audibly in sync from beginning to end. If you are using them to create a stereo or surround image, it should remain steady.

Once you have determined the drift between two cameras, you probably can apply the same correction to additional clips from the same cameras. You can re-use the calculated ratio, and you then need only a hand clap at the start of each clip.

OK, extra credit: here is my trick to get surround sound of a concert with a stereo recorder near the rear of the concert hall, for ambience, and another up front, for clarity. The speed of light is very much faster than the speed of sound, and so synchronizing on video images will produce an audible echo. Advancing the timing of the audio from the rear of the room to appear a few milliseconds later than audio from the front will produce a nice ambience in stereo, and good surround sound.

I have had speed correction hold steady through an hour-long concert with digital recordings. Analog recorders' speed stability is not good enough to maintain a steady stereo image without fancier processing, or at least, repeated re synchronization. Analog recorders' speed stability is is generally good enough though to align an an analog audio track to video, maybe with a few adjustments in the middle of a long recording..

![]()

![]()

Last Updated: by John Allen